I expect most people will already have some familiarity with Malala Yousafzai. In case you've been living under a rock, though, Malala is a young Pakistani woman who, at the age of 15, was shot in the head by the Taliban for her outspoken support of the right to education of children, including (especially) girls, who are often denied the right due to their gender. Miraculously, she survived the assassination attempt, and following her recovery, has continued to campaign in support of education. Now, at age 17, she has an impressive list of accomplishments and accolades to her name, including most recently becoming the youngest Nobel laureate in history after jointly winning the 2014 Peace Prize with Kailash Satyarthi, another activist for children's rights.

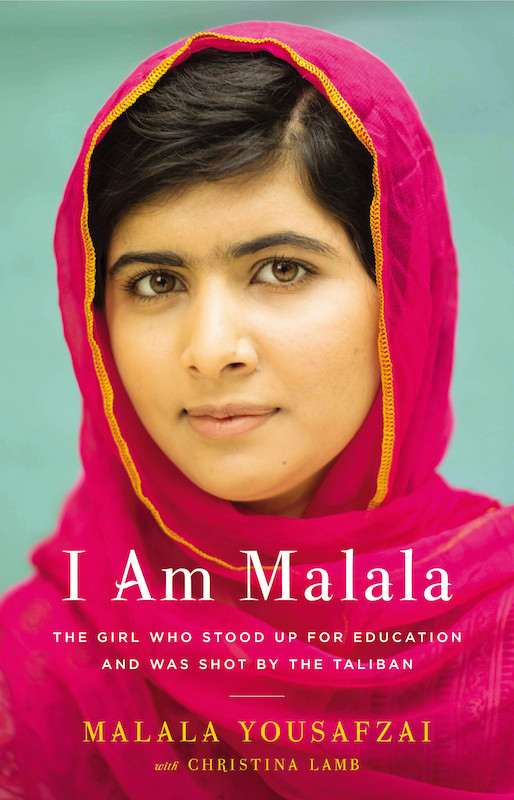

I Am Malala: The Girl Who Stood Up for Education and Was Shot by the Taliban, written jointly with award-winning foreign correspondent Christina Lamb, is Malala's autobiography. It chronicles her experience growing up in Pakistan's Swat Valley, the invasion of the Taliban into the area and her life under their rule, their attempt on her life, and her recovery and continuing efforts in support of education.

Before I continue, I have a caveat about this review. Reviews always contain elements of subjectivity, and there's nothing wrong with that per se: art, after all, is in the eye of the beholder. But a reviewer must endeavor to keep his own biases in check, and in particular, to separate his opinion of the creator from his judgment of the creation. In that respect, this review is difficult to write. I believe that Malala Yousafzai is the most courageous and heroic person alive today, and that her campaign has the potential to be among the most important activist movements of the 21st century. The emancipation and education of oppressed, powerless and impoverished women and girls in developing countries is vitally important to global stability and progress, and Malala has become not only an internationally-recognized figurehead for this struggle, but also, through her foundation and her speeches, one of the most important leaders in effecting a solution.

Naturally, then, I find I have a hard time criticizing Malala's work, and you should bear that in mind as you read this review. Despite any effort to the contrary, I will likely be more forgiving to this book than I would be to a book written by someone for whom I did not have such great respect.

It is unfortunate, then, that I must admit that this book took me almost a year to read, and not due to its length: even including a short glossary and timeline, it's barely more than 300 pages. The problem was that I just didn't find the first third of the book very interesting, so I started reading it very slowly, and then eventually put it down for a long time, only returning to it recently.

The first chapters of I Am Malala mainly serve as context for the rest of the book. Malala first describes the history of Pakistan and of her family, including much of her father's life before she was born. Her father, Ziauddin Yousafzai, is shown to be an ambitious and courageous person in his own right: his own dream was to be an educator, and as a young college graduate, he quickly progressed from teaching English in a private college to setting up his own school. He then tenaciously oversaw his school's development into a sizable and successful institution, despite many setbacks including considerable financial hardship and a natural disaster which all but destroyed the school building.

Malala also describes her father's respect for women, which no doubt played a formative role in her iron-willed personality, and which she contrasts with the rest of Pashtun culture:

For most Pashtuns it's a gloomy day when a daughter is born. My father's cousin Jehan Sher Khan Yousafzai was one of the few who came to celebrate my birth and even gave a handsome gift of money. Yet, he brought with him a vast family tree of our clan, the Dalokhel Yousafzai, going right back to my great-great-grandfather and showing only the male line. My father, Ziauddin, is different from most Pashtun men. He took the tree, drew a line like a lollipop from his name and at the end of it he wrote, "Malala." His cousin laughed in astonishment. My father didn't care.

Much of the rest of the opening of the book describes Malala's life in Mingora, from broad details about the general character of life in Swat (which will probably seem to most Western readers to be a peculiar mix of semi-modern technology, patchwork infrastructure, and ancient cultural traditions), to specifics such as her reputation in school as a talented and dedicated student. All of this is necessary background, particularly for Westerners such as myself who haven't the slightest clue what life in Pakistan is like, so I don't fault Yousafzai and Lamb for including it in the book—but, well, it's just not very interesting to read. Perhaps it's the linear, matter-of-fact way in which it's written, or perhaps it's the marked similarity of Malala's life before the Taliban occupation to that of a typical schoolchild, but I found myself struggling to get through this section.

And yet, peculiarly, this section also seems to be short on some basic factual details; for instance, until I looked it up for this review, I had pictured Mingora as a small, rural city. In fact, though, its population was 175,000 in 1998—sixteen years ago, so it's likely grown considerably since then. The city I grew up in has less than half that population today. Thus, my perception as I read the book was greatly skewed in this respect, but it needn't have been given all of the other details provided about Swat and Mingora.

The pace of the book picks up as the Talibanization of the Swat Valley begins in 2007, when Malala is ten years old. Maulana Fuzlullah, now a highly ranked militant leader in the Pakistani Taliban, started a radio broadcast in which he professed his interpretation of Islam. Fazlullah's broadcasts started innocently enough:

He used his station to encourage people to adopt good habits and abandon practices he said were bad. He said men should keep their beards but give up smoking and using the tobacco they liked to chew. He said people should stop using heroin, and chars, which is our word for hashish.

Over time, though, Fazlullah became increasingly radical and fundamentalist: claiming that sinful actions such as "listening to music, watching movies and dancing" had caused a recent earthquake; instructing women to never leave their homes except in emergencies, and to always be veiled while in public; and referring to the Pakistani government as infidels, stating that "his men would 'enforce [Sharia law] and tear [government officials] to pieces.'" By 2007 Fazlullah had become a powerful and influential figure within the Pakistani Taliban, and on the 12th of July, following the Red Mosque siege, he declared war on the Pakistani government.

The Taliban continued to spread throughout the Swat valley. By 2009, the Talibanization had become so widespread that even local politicians, including the area's deputy commissioner, were involved: "When the highest authority in your district joins the Taliban, then Talibanization becomes normal." As they gained more and more political power, they also began enforcing their strict interpretation of Islamic doctrine through threats and outright violence. They issued an edict banning the education of girls, and meted out brutal punishments for "immoral" acts such as dancing or wearing clothes "incorrectly." There were bombings, executions, and public whippings.

It was during this time that Malala began writing, at the behest of the BBC, "a diary about life under the Taliban." This diary was published online as part of the BBC's coverage of the situation in Swat, but Malala used the pseudonym "Gul Makai" due to the great danger inherent in criticizing the Taliban. The diary only lasted until a few months, though. The Pakistani army had been trying for some time, noncommittally and mostly ineffectively, to push back the Taliban, but after a brief ceasefire, in May of 2009 they launched a full-scale operation, "Operation True Path, to drive the Taliban out of Swat." This resulted in an exodus of civilians from the valley, and thus Malala and her family became "Internally Displaced Persons," forced to leave their home for nearly three months while the army effected its campaign to take back Swat.

The campaign ended with the army claiming victory in July of 2009, and Malala and her family were able to return home. But, predictably, the army's successful campaign could not completely or permanently rid the valley of Taliban:

In Swat we began to see more signs that the Taliban had never really left. Two more schools were blown up and three foreign aid workers from a Christian group were kidnapped as they returned to their base in Mingora and then murdered. We received other shocking news. My father's friend Dr. Mohammad Farooq, the vice chancellor of Swat University, had been killed by two gunmen who burst into his office. Dr. Farooq was an Islamic scholar and former member of the Jamaat-e-Islami party, and as one of the biggest voices against Talibanization he had even issued a fatwa against suicide attacks.

...

Once again people started worrying that the Taliban were creeping back. But whereas in 2008-9 there were many threats to all sorts of people, this time the threats were specific to those who spoke against militants or the high-handed behavior of the army.

"The Taliban is not an organized force like we imagine," said my father's friend Hidayatullah when they discussed it. "It's a mentality, and this mentality is everywhere in Pakistan. Someone who is against America, against the Pakistan establishment, against English law, he has been infected by the Taliban."

Despite this, Malala continued speaking at events in support of education and peace, and continued to gain national and international attention, including winning Pakistan's National Peace Prize—a brand new award for which Malala was the first recipient ever. But as we now know, this stubborn refusal to be silenced would come at great cost to her.

On Tuesday, October 9th, 2012, Malala was shot in the head by a young Taliban gunman as she rode the school bus home. This chapter, in contrast to the terrible event it recounts, is probably the best written in the book. Malala describes every minute detail of the moments leading up to the assassination attempt: the sounds from the shops along the road, the smell of the air, and then the sudden, ominous absence of people in the street. The style here precisely communicates the feeling of a memory of a terrible event: the way time seems to slow leading up to it, and how vividly we recall the mundane circumstances and sensations it becomes associated with. Even though this is the part of Malala's story that everyone already knows, it's pulse-quickening to read in her own words, and at this point the book becomes very hard to put down.

The rest of the book, which comprises about a fifth of its total length, describes Malala's treatment and recovery, and briefly illustrates her new life in Birmingham, England. Living in England has given Malala the opportunity to return to school, and to continue to speak in support of education for children, without being in constant danger. Nevertheless, she misses her home in Swat, and already has aspirations to return to Pakistan:

I know I will go back to Pakistan, but whenever I tell my father I want to go home, he finds excuses. "No, [dear one], your treatment is not complete," he says, or, "These schools are good. You should stay here and gather knowledge so you can use your words powerfully."

He is right. I want to learn and be trained well with the weapon of knowledge. Then I will be able to fight more effectively for my cause.

Here again, though, I wish I Am Malala provided more detail. Malala's cause is clear, as is her fearless determination in pursuit of it. Still only seventeen years old, she already has the recognition and support of the international community, and a non-profit foundation in her name working towards her dream of safe, free education for all children. But achieving this will be no easy task, and I wish the book provided a more complete picture of Malala's vision. Besides the overt threat of terrorist groups such as the Taliban, Malala and her foundation will have to contend with poverty, war, cultural impediments to learning, suspicion of the West and its influence, and innumerble other challenges. She has a long fight ahead of her. What is her plan?

Perhaps this is a lot to expect from a seventeen-year-old. But then, Malala has very clearly demonstrated that she is no ordinary seventeen-year-old. I'm sure she has given some thought to these issues, and I wish her book had provided more insight in that respect. For instance, she briefly mentions a now-infamous letter she received from Taliban commander Adnan Rashid, who claims she was shot for espousing what the Taliban view as a pro-Western, anti-Islamic ideology. She barely dedicates a paragraph in response to this, but even here in the West there are people who take Rashid's words at face value, as if his stance is perfectly legitimate and reasonable. This is a problem that Malala will likely have to contend with for as long as she continues to fight for her cause. What will she do to solve it? I can only hope that details such as these will be the subject of another book.

Much as I'd like to, I can't say that I Am Malala is among the best books I've ever read. It is linear and factual to a fault, some of it written almost like a narrated CV, and is at times ponderously paced. It seems to me to be more about what Malala has done than who she is; for an autobiography, it feels curiously impersonal. That said, the latter two-thirds of the book are still an enjoyable read, at least for those who want to know more of Malala's story. Most importantly, whatever quibbles I have with the way I Am Malala is written, it may well be one of the most important books I've ever read, because like Malala herself, it is a testament to what can be accomplished through hope, dedication, and perseverance.

I hope, and expect, that we will only hear more and more about Malala Yousafzai as the years go on.