I got the new Fitbit Ionic a few weeks ago, and I'm generally pretty happy with the device. I'm in the process of writing a full review of the Ionic, but I realized partway through that I had written quite a lot about the SDK, which many people probably won't be interested in. Hence, I decided to make that into its own post. In the meantime, if you're looking for a review, I would recommend reading DC Rainmaker's. He's a much more serious athlete than I am, and he reviews fitness gear semi-professionally, so he's able to put the devices through much more rigorous tests and go into detail about things like heart rate and GPS accuracy, which I won't be doing.

Anyway, the Ionic being Fitbit's first real smartwatch, I was eager to check out the SDK and dive into app development. And, well, I've tried to do so, but so far the results haven't been great. I think this is partly just because the platform is very new, and partly because of some questionable technology decisions that Fitbit made. Although it's too early to really evaluate the success or failure of the Ionic, or of FitOS an app platform, I think it can still be instructive to look at some of the choices that Fitbit made in designing the device and the OS, what effects they're having on developers now, and why I think they may prove to have been suboptimal choices.

Battery life was clearly the foremost concern for Fitbit when they designed the Ionic, and the technology decisions reflect that. Whereas the Apple Watch series 3 has a dual core CPU with a maximum clock speed of at least 780 Mhz, 3D graphics acceleration, and a rumored 768MB of RAM, the Ionic contains the humble Toshiba TZ1201XBG, with a meager maximum clock speed of 120Mhz1. The battery life of the two devices reflects these hardware differences: the Ionic lasts 4-5 days on a charge, whereas the Apple Watch lasts a maximum of 2 days. Personally, I think this was a great choice by Fitbit. Although the Apple Watch is inarguably a more capable "smartwatch," its two-day maximum battery life is an absolute deal-breaker for me, which is one of the primary reasons I bought the Ionic instead.

With the hardware itself being so thoughtfully designed to maximize battery life, it strikes me as a bit odd that Fitbit chose JavaScript as the sole language for app development on their platform. JavaScript is not known for being a high-performance, memory-efficient programming language; historically, it has been quite the opposite. Of course, it's not the language itself that matters so much as the interpreter, and modern JavaScript engines like V8 and Chakra have made extremely significant performance improvements compared to how slow JavaScript interpreters used to be. The Ionic, for its part, uses an engine called "JerryScript", which is designed specifically for IoT devices and allows JavaScript to be precompiled to bytecode; it boasts that it can run in environments with less than 64KB of RAM and less than 200KB of ROM. I'm not sure where the name comes from; contrary to what you might expect, the project's main contributor does not appear to be named Jerry. For me, the name just conjures images of Jerry from Rick and Morty:

Uh, anyway, JavaScript is still orders of magnitude slower than C and C++ for most workloads, and when you're concerned about energy efficiency and performance on a device with a 120Mhz single-core CPU, that difference matters. I freely admit that I am biased in favor of languages like C and C++, which are as close to the metal as you can get in a high-level language. Some would consider this preference anachronistic, but it's undeniable that there are still many places where maximizing performance really does matter. Embedded applications are one of those places, and I'm fairly confident that on the Ionic, using native code could have offered even better battery life, or perhaps improved performance, which is sometimes suboptimal even in the built-in apps.

Similarly, all UI on the Ionic is done using Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG). SVG is a lot easier to use than requiring developers to render their own UI, but it's also a lot less flexible than just blitting pixels to the screen. The minimum benchmark that any modern computing device should be able to pass is whether or not it can run DOOM, but between the poor performance of JavaScript and the inflexibility of SVG, I don't see that happening on the Ionic any time soon.

In fairness, Fitbit had a difficult problem to solve in developing an SDK for a smartwatch which supports multiple "companion" devices (i.e. iOS, Android, and Windows devices which communicate with the watch). First, there's the technical problem to solve of enabling the device to communicate with those three platforms, each of which has different restrictions on what apps can do. But perhaps equally important is the challenge of making the SDK easy and convenient enough that people will actually want to develop for it. Having an app platform is meaningless if nobody actually writes apps for it, and as Microsoft found out with Windows Phone, it can be very hard to attract developers to your platform if you're not already in a dominant (or at least strong) market position. Fitbit has been very successful with its cheaper wearables, but this is their first real smartwatch, and between Apple, Garmin, Suunto, Samsung, and dozens of others, there's a lot of competition.

With that in mind, it's tempting to think that a platform can be differentiated by making it very easy to develop for. I assume this was one of the primary factors that weighed into Fitbit's decision to use JavaScript: it's generally considered to be a pretty easy language to learn and use, and since it can be run within the official Fitbit app on the phone or PC, it allows developers to write "companion" modules for their watch apps in the same language that the watch app itself is written in. (This is often cited as an advantage of node.js—you can write your code in the same language on the server and the client. Personally, I've never understood why one would want to write JavaScript on the server, but that's just me.) The ability to easily create companion modules is important, since the watch can't directly communicate with the Internet; all Internet access must use the companion app as a proxy. (The Ionic does have WiFi, but it seems to only be used for syncing must and downloading firmware updates. As I understand it, this is because WiFi consumes too much battery.)

The problem is that I don't think it's actually true that you can attract developers to your platform on the basis of it being easy to develop for—at least, not solely or primarily on that basis, and not the kind of developers you actually want to attract (that is, skilled developers who know what they're doing). The whole open source community is a testament to the insane amount of work that some software developers are willing to do for free, but everyone needs to eat. Developers will come to a platform if it provides a money-making opportunity, even if it's difficult to develop for; conversely, the easiest development platform in the world won't help if it has no users. With that in mind, it's also concerning that the FitOS platform has no built in way for app developers to charge for their applications.

And in any case, the biggest problem is that currently, the Ionic isn't actually easy to develop for, because the SDK is seriously short on features and extremely buggy. The web-based toolchain can also be pretty painful to use. In no particular order, here are some of the issues I've run into in the process of trying to develop a simple app, along with a few other problems that other developers have mentioned in the forums or in Discord:

- The DOM for an app's interface cannot be modified at runtime, so the only way to change your UI dynamically is to hide and show pre-existing elements. (Limited support for being able to spawn copies of existing elements is coming.)

- There is currently no built-in support for multi-page applications. Again, you just have to show and hide different elements to achieve the effect of multiple pages.

- Although the watch CPU appears to support hardware accelerated AES and SHA256, this isn't exposed through any API, so cryptographic operations require the use of third-party JavaScript libraries and end up being unusably slow.

- I cannot get the OAuthButton component to work in my application settings, which means I can't authenticate to basically any web service. This might be iOS-specific; one of the Fitbit developers mentioned that their QA had reported something similar, so hopefully they're looking into it. Another developer mentioned having trouble getting OAuthButton to work with Fitbit's own REST APIs! Unfortunately, there are currently no examples of how this component is supposed to work. [Edited 2017-10-22] This appears to be fixed now.

- There is no emulator available, and no way to test the companion app or Settings page in the browser. This is an annoyance in general, and it seriously exacerbates the OAuthButton issue makes it really hard to debug any issue with REST APIs, because it also seems to be nigh-impossible to capture decrypted HTTPS traffic from an iOS device. (Granted, that last bit isn't Fitbit's fault at all, but it also wouldn't be an issue if the OAuthButton just worked.)

- PNGs are automatically converted to a proprietary hardware-accelerated format, but JPGs are not hardware accelerated so they take forever to load and can actually cause crashes or hangs if they're too big. This isn't a big deal for static images within the app, but what if you want to show content from the Internet?

- Communication between the watch and the "companion" app running on the phone seems to have some reliability issues. Sometimes the companion seems to just not launch at all.

- There is no way to "push" data from the companion to the watch. The watch app has to request the data, which means you need to poll for it if you don't know when the data will be available. (In fairness, this might be an iOS limitation.)

- Some APIs having confusing asymmetries. For instance, apparently in order to send a file from the companion app to the device, you need to manually CBOR-encode the contents before sending it. But when reading the file on the other side, it is decoded for you automatically.

- Documentation is fairly limited; for example, a lot of APIs have parameters that aren't well-explained, so you kind of have to guess what they do and then figure it out by trial and error.

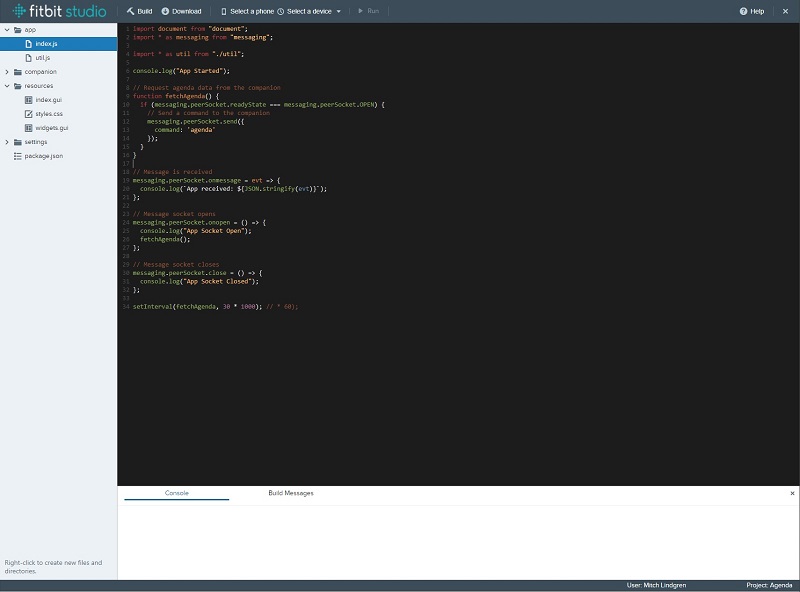

- There is no local toolchain that you can install on your PC or Mac; there is only a web-based IDE which builds and deploys your app for you. This means no Git (unless you download copies of your code every time you make changes), no inline diffs, no using your own text editor with your own keyboard shortcuts, and no working on your app if you're offline. Some people have also reported connectivity issues when trying to get the watch to talk to the IDE.

- The IDE does not support breakpoints, performance profiling, or other such tools that you'd expect

from a modern development environment. I hope you enjoy debugging using

console.log(...)! By the way, there's a (relatively small) limit to length of string you can log.

I could go on, but I'm sure you get the point. Fitbit is aware of many (hopefully most) of these issues and is already working on many of them, and I have to commend their developers for being very responsive and involved in the community. There's an unofficial Discord channel where a few of the developers are very active in providing advice and investigating issues raised by the community. It's nice to have such a direct line to the development team; when interacting with a bigger company, you usually have to go through six layers of customer service and escalation engineers before you get to talk to an actual developer. Unfortunately, the downside is that the handful of Fitbit developers who are going above and beyond by fielding SDK questions during and outside of work hours can't possibly hope to keep up with the volume of requests they're getting, especially given how many issues there are right now. A public bug tracker would be nice so that we have a definitive source for which issues are being tracked...

It's frustrating that the SDK wasn't more complete at release. I'm sympathetic to the need to get the device out the door, especially given that Fitbit is facing stiff competition from bigger companies with vastly more resources. However, that fact only compounds my feeling that building a brand new JavaScript-based app platform was probably the wrong decision. In general, I'm of the opinion that any new app platform should start by exposing APIs that can be called from native code, and providing a toolchain that allows developers to compile C and/or C++ into the platform's native instruction set. Not only is this more performant, but it's easier to do: since you need to at least partly implement your APIs in native code so that they can talk to onboard devices, adding a scripting interface is just extra work. Once the (public!) native APIs are working, stable, and reasonably complete, you can build a managed code SDK on top of it… or just sit back and wait for someone else to do it for you.

This appears to be what Pebble did, as they provided a C API to create "watchapps and watchfaces," and a JavaScript API which could only be used for watchfaces. Given that Fitbit acquired Pebble last year, reportedly primarily for the purpose of using their code and expertise to build FitOS, I don't know why Fitbit didn't just literally rename all the Pebble APIs and call it a day. I haven't actually done any Pebble development, so maybe I'm missing some major issues, but from a quick perusal of their documentation, their APIs look pretty solid, and they're obviously a lot more mature than Fitbit's new platform is. Pebble's users certainly seemed to be happy with the platform (to the point that many of them were very vocally disapointed when the company was acquired by Fitbit). Plus, Pebble had Android and iOS SDKs to allow third party apps on those platforms to communicate with the watch, in addition to a JavaScript-based SDK that ran as part of Pebble's own Android/iOS app. This approach appears much more flexible and powerful to me. Perhaps eventually Fitbit will follow suit, but at this point I'm not holding my breath.

So, what's the takeaway of all this? It's not that the Ionic is a bad device, or that its app platform is doomed to failure, or that Fitbit has bad engineers. I don't think any of those things are true. What I would like to communicate—and this will probably be a running theme in all of the CS-related writing I ever do—is that technology decisions really matter. Programmers are notorious for getting into religious wars about their favorite languages, and evangelizing your preferred technology too hard makes you come across as an asshole. I'm probably already guilty of this. But on the other hand, I feel that there's a strange sort of postmodern stream of thought in CS that it doesn't really matter what languages or technologies you choose to use in any given case, because they're all more or less equally capable, and that's… just not true.

Yes, there is a sort of isomorphism between any two Turing-complete languages, but in practice you can't simply gloss over the performance implications of using, say, JavaScript (or even Java) instead of C or C++. This might sound blindingly obvious, but remember that even huge companies are subject to this mentality, sometimes with disastrous results, as was the case with Windows Longhorn. (It also runs rampant in college CS programs, which is why it's notoriously difficult to hire college graduates who are comfortable with C or C++.)

Lest I come off as too much of a native code zealot, I'm not saying that native code is always the right choice. If you're writing a web application, or anything else that involves a lot of text manipulation, database interactions, or (de-)serialization of dynamic objects, you're probably crazy if your tool of choice is C++. Even just writing a client for REST APIs in C++ is not very fun (I know this from experience). But, particularly if you're building an app platform or a modding system or something like that, it's better to offer third-party developers as much flexibility and power as you can, rather than painting yourself and everyone else into a corner to start with. Remember that you can always just export C APIs and provide bindings to call them with your favorite scripting language. It's quite a bit more difficult to do the other way around.

-

The first personal computer I ever used was a Macintosh LCII, which had a clock speed of 16 MHz. That was 20-some years ago. If it doesn't blow your mind that we can now fit a CPU an order of magnitude more powerful than that in a watch, and make it run for several days on a tiny battery while powering several other sensors... well, it should! ↩