If you've ever read OkCupid's popular OkTrends blog, you're already familiar with the work of Christian Rudder. As OkCupid's resident mathematician and one of its founders, he has been writing for years about statistical trends related to dating and attraction, leveraging OkCupid's vast database of traits about, and interactions between, its millions and millions of users. OkTrends produced numerous interesting and surprising results, and it developed a significant following before going quiet for the better part of three years beginning in 2011.

Now, Rudder is back with Dataclysm: Who We Are When We Think No One's Looking, which expands on OkTrends by drawing from a wider variety of sources (including Facebook, Google, and Twitter, in addition to OkCupid and other dating sites) and discussing a more diverse set of topics. Organized into three themed sections which focus on, respectively, unity, division, and individuality, the book explores what data can tell us about gender, sexuality, race, identity, community, and other sociopolitical questions. The discussion is consistently balanced and neutral, which is important when dealing with such potentially charged subjects, but Rudder also manages to inject enough of his personality and characteristic style to keep the book enjoyable throughout.

Indeed, the OkTrends blog was popular not only for the fascinating observations it produced, but also for Rudder's accessible and entertaining writing style, and he continues this to great effect in Dataclysm. No mathematical or statistical knowledge whatsoever is required to understand the topics discussed in the book; data are presented in the form of simple graphs and explained using plain English with a minimum of jargon.

Unfortunately, this focus on accessibility also gives rise to my biggest criticism of the book: on the spectrum of "pop science" writing, Dataclysm is decidedly more pop than science. In and of itself, that isn't a problem per se, but in many instances I felt that a more methodical approach could have led to a broader and more productive discussion. Rudder is not nearly thorough enough in describing the methodology by which he arrived at his conclusions, nor in presenting (or at least making available) salient facts about the data he used, nor in exploring alternative hypotheses.

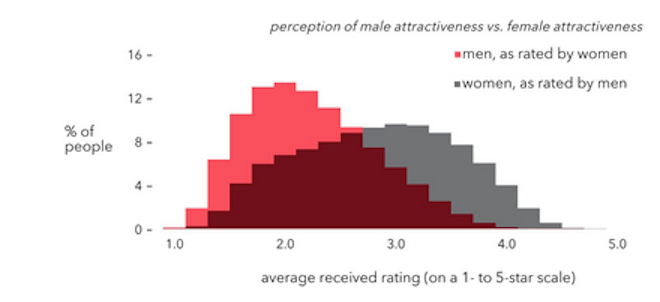

For example, consider the following graph of the "perception of male vs. female attractiveness" from the introduction. On the x-axis is the average of all ratings (on a 1-5 star scale) received by a user, and on the y-axis is the percentage of all users that received that average rating:

Copyright 2014 Christian Rudder. Used under Fair Use.

Rudder explains:

Our real-world data [of women's attractiveness as rated by men] diverges only slightly (6 percent) from this formulaic ideal [of a symmetric beta distribution] ... it implies that the individual men who did the scoring are likewise predictable, centered, and above all, unbiased... It's practically common sense that men should have unrealistic expectations of women's looks, and yet here we see it's just not true.

The red chart [of men's attractiveness as rated by women] is cenetered barely a quarter of the way up the scale; only one in six guys is "above average" in an absolute sense... [as an analogy,] translate this plot to IQ, and you have a world where women think 58% of men are brain damaged.

This is certainly interesting data in its own right, but I don't think Rudder goes far enough in exploring what it means or why it might be the case. By comparing against a similar random sample from a social network, he determines that it is not because men on OkCupid are unusually ugly—this pattern persists beyond dating sites. His hypothesis is simply that "men and women perform a different sexual calculus," and, quoting Harper's Magazine, he notes that "women are inclinded to regret the sex they had, and men the sex they didn't."

This is certainly a plausible explanation, and it's intuitively appealing, but it also seems like a bit of a cop out based stereotypical beliefs about gender differences. I'd like to see data about how straight men and women rate the attractiveness of people of their own gender—although not directly analogous since it would be divorced from sexual desire, I suspect that the results might raise questions about Rudder's hypothesis here.

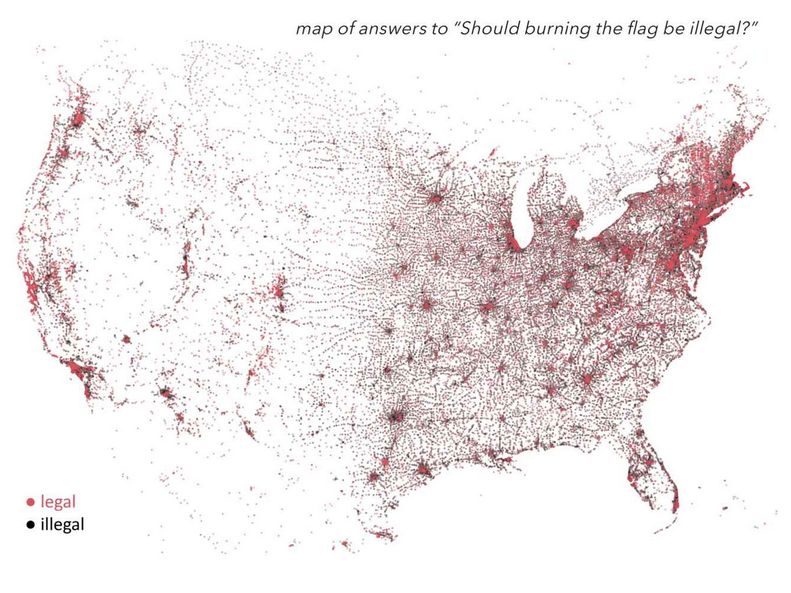

In the interest of fairness, I must restate that his discussion takes place in the book's introduction, so it's not representative of the length at which other findings in the book are discussed. Most likely, it's just meant to pique the reader's interest and serve as an example of the kind of data the book will examine. Nevertheless, similar issues persist in later chapters of the book. Consider this map of responses to the question "Should flag burning be illegal?" among OkCupid users:

Copyright 2014 Christian Rudder. Used under Fair Use.

Rudder claims that this map demonstrates that "this is truly a nation defined by its principles, or, as you can see, two nations: Urban and Rural." But to my eyes, the colors overlap too much to make a meaningful distinction; this really just looks like a population map. What's more, it appears to include Canadian responses even though I can only assume that Rudder is referring the US when he writes "a nation," singular. And again, there is no discussion of important methodological questions or possible confounding factors, such as whether OkCupid's user base is disproportionately urban (which doesn't seem unlikely to me), and whether or not that was corrected for if so.

Rudder anticipates criticism of his decision to eschew "statistical esoterica," and defends it as follows:

I don't mention confidence intervals, sample sizes, p values, and similar devices in Dataclysm because the book is above all a popularization of data and data science... But like the spars and crossbeams of a house, the rigor is no less present for being unseen. Many of the findings of the book are drawn from academic, peer-reviewed sources. I applied the same standards to the research I did myself...

I fully accept that there is a place for and a value to "popularization" of scientific fields, and that it's sensible to exclude complex statistical measures which would be meaningless to most readers... from the main body of the text. But I don't see why Rudder didn't even see fit to include these as footnotes or endnotes, which the book does have. And with respect to the academic research used, Rudder relegates all of his citations to endnotes, which usually link back to the text referring to them, but are not linked to from that text, which can make it very hard to match up specific statements with the studies supporting them.

All of this criticism notwithstanding, I really enjoyed reading Dataclysm, and I would heartily recommend it to anyone interested in gaining insight into the social and political identities of (primarily American) Internet users. Anyone interested in the burgeoning field of data science would also likely enjoy this book. It's just worth noting that some of Rudder's conclusions should be taken with a healthy dose of skepticism until they can be replicated with rigor that is seen.